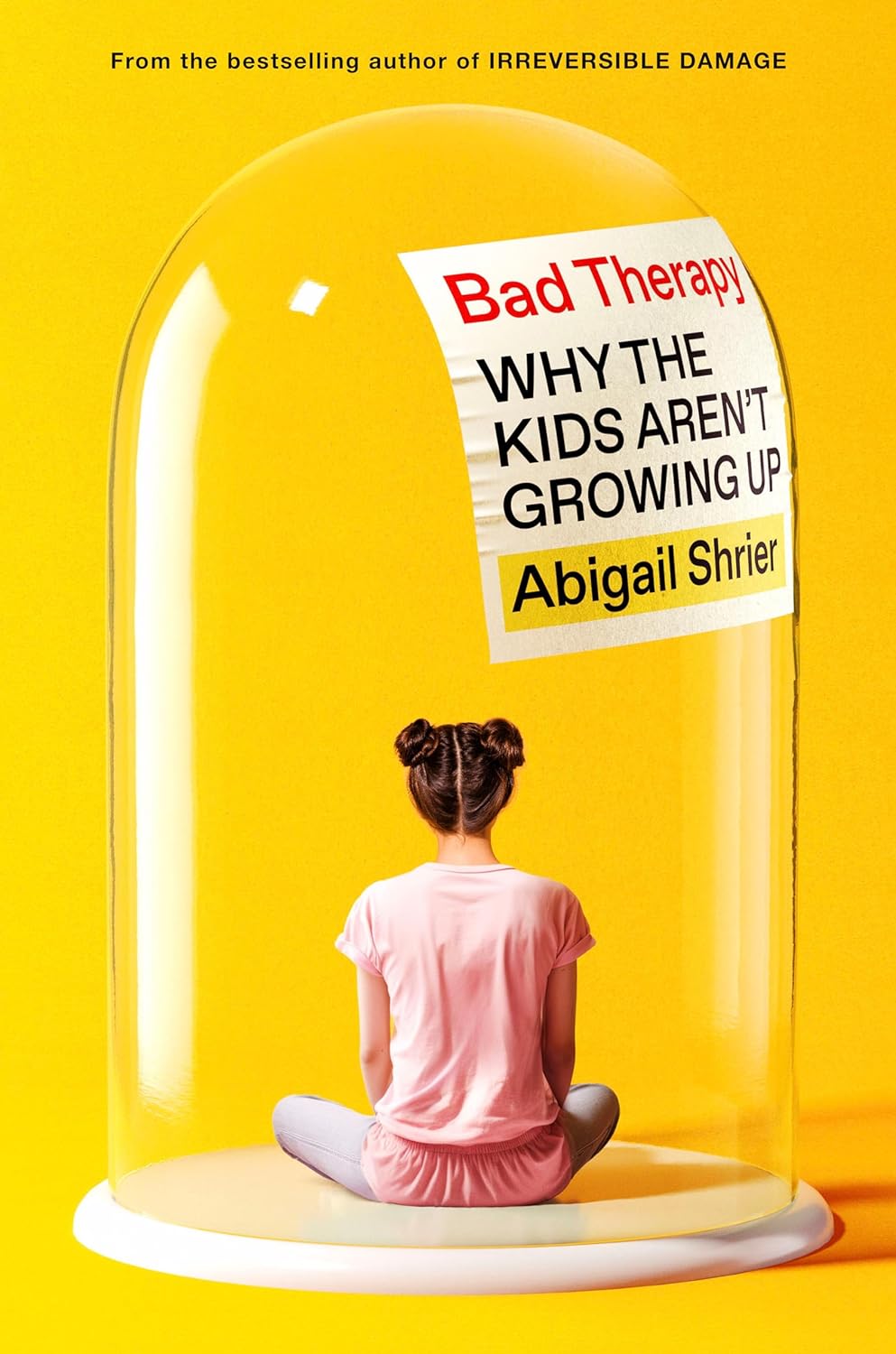

I started hearing about the book Bad Therapy by Abigail Shrier a few weeks ago when a friend asked me about it. “Hey, I heard this woman on a podcast say that therapy is bad for kids except in extreme cases…”

I had another friend bring it up a little later and tell me that they were frustrated because their wife read it and didn’t want their kids to go to therapy, and he thought they should be going. Then I met someone who told me their kid would never go to therapy because they heard her on the Joe Rogan Experience or the Jordan Peterson Podcast (confusion is on my part, not theirs; I simply can’t be sure which podcast they mentioned).

At some point, I knew I would read it and ponder it. I only thought a little about whether or not I would review it. I rarely review books publicly, and I’ve even stopped giving books stars on my Goodreads account. But this book needs to be reviewed, and its subject matter needs to be discussed.

Overview

I have been telling my friends for years that conservatives were going to be coming for therapy. And in many ways, it’s deserved. We have more money, time, resources, and energy focused on mental health and don’t have results that match. Therapy is mainly run by people with a liberal orientation to life and politics. As such, it is an easy target for conservatives to attack as our society seems to embrace the ever-dividing line of ideology in our country. But that doesn’t absolve therapy or therapists from answering legitimate questions about treatment, how we do it, and what outcomes we’re getting from our current efforts.

On Facebook, that ever-acerbically diverse place, I told a friend that I am glad we are being forced to have the discussion. It’s an important discussion to have. If we relegate something to the “we can’t discuss that” category, we enter dangerous territory that does a disservice to the whole. If only this book had been written in a way that would generate a discussion. But alas, it was not written to create discussion; it seems it was written to eviscerate as stupid any who disagree with her and win a fight you, the reader, may not have known you were entering when you picked up the book (or in my case downloaded the audible and kindle version).

The author makes some excellent points and rightly questions some societal practices. She rightly calls into question the reality that many educators do therapy-like things without training. She rightly questions outcomes.

She also loves stating her opinion as fact without research, and when she does use research, much of it is cherry-picked, as she ignores research that disagrees with her assertion.

I wanted to like the book, but from the very opening words of her book, I found things that conveyed to me that she wasn’t interested in a conversation. Throughout the book, she engages in the problematic reasoning and proclamations she is trying to call out. She calls out a lot of things that “might” and “could” bring harm while simultaneously ignoring how her few offered solutions “might” and “could” also bring harm.

Are there bad therapists? Of course. Are there bad school systems? Absolutely! Can they bring harm to those involved in it? I think that goes without saying. But that brings up the most frustrating aspect of this book; I would find a good point, a great one even, and it would be sandwiched between two terrible ones. She opens the book, telling us that there are some kids with “profound mental illness. Disorders that, at their untreated worst, preclude productive work or stable relationships and exile the afflicted from the locus of normal life. Theirs is a crisis of neglect and undertreatment. These precious kids require medication and the care of psychiatrists.” But not to worry! “They are not the subject of this book.” (p. xi). That sounds good, right?

Except that she seems to imply that the only kids who could ever possibly need therapy are the very few who are mistreated, abused, or neglected. And, of course, she fails to share her metric for that criteria while simultaneously attempting to poke holes into everyone else’s criteria unless they agree with her. Ultimately, it’s her universal jettisoning of therapy for kids that proves to be one of the book’s biggest problems. She conflates educational interventions with therapy, something that she rightly points out that proponents of therapy seem to do as well. Lastly, she seems unwilling to admit that there are bad parents out there and that there may be other more significant and more likely issues causing the problems she addresses.

The Bad:

Imagine if we found an investigative journalist who wrote something entirely made up and then used those examples to discredit all investigative journalists. That sounds preposterous, doesn’t it? And yet, in many ways, this author has done that.

She boldly proclaims that childhood anxiety has done nothing but go up over the last fifty years. And she’s right. She points to our emphasis on screening for and focusing on mental health as the likely and only culprit. Of course, as you have probably heard and maybe even said a time or two, “correlation does not prove causation.” I can statistically prove that Michigan’s ice cream consumption and drowning rates increase over the summer. That does not mean they are related.

And I have something else that can also track over those fifty years. Fifty years ago, divorce went mainstream. Casual sex went mainstream. We started to redefine family and lost our value of the family system. What was frustrating for me was that she came so close to catching this in Chapter 7 when she talks about her friends who forgot their math textbook at their dad’s house and couldn’t get it for a week. “They didn’t seem happier,” she laments and then goes on to blame therapy and schools.

It seems like looking at the Oakland Athletics or the Pittsburgh Pirates and concluding that all MLB teams are poorly run because those teams are poorly run.

Let’s talk about some specific problems with the book. In one section, she talks about ways one might do harm. This section is filled with misrepresentation of how therapy actually works. She cherry-picks some of the worst and then extrapolates that to all treatment. In one particularly egregious section, she writes that there is zero evidence to suggest that rumination is helpful. She cites a therapist who says he has never found it helpful with the people he works with in his practice. Which begs the question, who does this guy she’s quoting work with? Kids, right?

Nope. He works with convicts who are being reintegrated into society. Now, if someone used him or his research to prove rumination is helpful, would our intrepid investigative journalist trot that out there as contradictory evidence? I doubt it. She’d probably ignore it or point out that the issues and desired outcomes of working with convicts are different than working with children. And she’d be right. It makes one wonder why she trots it out then to support her case. Her case should have copious amounts of supporting evidence because, as she repeats time and time, there’s zero evidence to contradict her. In this section, like in many of her sections, she only gives half the story. Paul Harvey could write a companion book for her. You see, if all we do is ruminate on the bad things happening in our lives, or if all we do is ruminate on our troubles or trauma, she is correct. There is very little value in that, and despite her proclamations to the contrary, there are many therapists who would not advocate for rumination only. Her gesticulations that all therapists do is want people to think about their depressing moments is not only silliness; it is practically libelous. Are there therapists that do just that? Of course, just as journalists lie to get a story. She seems to underestimate the power of just talking about something as well. Rumination can be extremely helpful, and denying that could be harmful (see what I did there, Abigail?)

We turned out OK!

As I read it, the essence of her argument is that our parents did these things, and we turned out OK. We need to go back to that way because of this observation. I found it interesting that she does this while saying she’s blaming therapy and not parents, but most of the book is taking potshots at parents in an almost mocking tone that they don’t do it the way she wants them to. She rightly points out that parents want their kids to be their source of emotional energy and sustenance, which is almost always problematic. She rightly points out that ADHD has treatments that are not medicine-based and that those medicines bring their risks. She takes the industry to task for refusing to discuss the idea that ADHD might not be a disorder. But she doesn’t do it in a way that causes the reader to think she actually wants to discuss it.

The book is littered with proclamations that parents have given up their parenting mojo to the “experts,” but then she fills the other pages with we should do it this way because I think so, and this expert agrees with me. It’s maddening!

In my section on the good things in this book, I mentioned that she rightfully calls out schools and school systems, seeming to want to be the number one influence in our children’s lives while ignoring that there are bad and disconnected parents. However, this book has a bigger problem: she glosses over the disconnected parents and blames everything but the parents. She blames the school system; she blames therapy. She blames liberal ideology, but she never actually stops and asks why our parents are not connected to their kids. She does this in the middle of actually presenting the answer. She talks about how overscheduled families are and how we have sold out to sports and personalized band lessons, and then somehow brings that back to being the school’s fault and therapy’s fault as the school and therapy force the parents to make these decisions. She calls for personal responsibility while simultaneously deflecting responsibility from the very people making the decisions she is decrying.

Perhaps my favorite part of the book is how she ends chapter 10 by telling the reader that she does not know how to raise their child, but they do! The audible version is almost laughable, especially the faux empathy she puts in those words, because the next chapter resumes her ranting about what parents should and should not do. “Stop doing this! Start doing that! Why would you do this? What’s wrong with you? Stop doing that!” The entire chapter goes on in a staccato fashion. You are a fool if you trust the experts, but trust me and my experts right after I tell you that I don’t know how to raise your child, but you do.

You see, the problem is, according to our unintended expert here, is that we have replaced spanking with medicine. The reason we have to medicate our kids is that we stopped spanking them.

Well, Abigail, should I call you Abby? I don’t spank my kids, and I don’t medicate them, and oh, by the way, they’ve turned out pretty good. Now, I know that’s anecdotal evidence, but taking an anecdote and liberally spreading it around as fact clearly does not bother this author at all. And she goes further! She claims there is “zero research to suggest that spanking brings harm to children!” Come on, Abs! Really? Zero? None? Nada? There isn’t a stitch of research out there to suggest that spanking can bring harm to kids. She sticks to this story while lauding at least two people who raised “amazing adults” who didn’t believe in spanking.

Perhaps the most frustrating part of reading this book was that although the author has some good things to say, they will be lost in the cacophony of her vitriol and slathering of opinion as fact, her cherry-picking of research, and her half-truths. Her section on parent estrangement reads as though there are no bad parents. Almost all parent estrangement is because of bad therapy, which seems to be her cry.

In one chapter, she points out that in “some circumstances,” self-harm behavior might not be that big of a deal. And she’s right. But she leaves a big hole in her rant. What about the circumstances where they are a big deal? What about the circumstances where someone could be in real danger? She gives zero direction on what those circumstances might look like except to say, “Keep your authority!” and something akin to “Use your best judgment.” But then she tells people to follow her judgment.

Perhaps the biggest lie in this book

Perhaps the biggest lie in this book and others like it is that therapist don’t ever want their clients to stop coming to therapy. I talk to my clients about what it will look like to stop therapy in the first session, and I am confident I am not the only one. She acts like therapists don’t want you to get better. They want you to be symptomatic forever, she walks out a kid who resented therapy as a kid and come to the conclusion as an adult. In this example, our now adult who was forced into treatment as a kid ruefully tells us, “Therapy is like learning to ski by focusing on the trees.” She closes that deep thought with an exclamation and then lambasts how the parents disagree with her obvious conclusions in this book. She condescendingly uses the words “we parents” but then points out that she isn’t part of the we.

Are there bad therapists? Of course. Are there therapists that are so bad they don’t want their clients to terminate? Of course.

But all I need is one adult who appreciated his time in therapy as a child to refute her point on the kid resenting it.

She concludes the book with a rousing chapter where she makes some excellent points. But then she goes into a lather of calling therapist interlopers. She laments that parents are identifying their kids by their diagnosis. This is an excellent opportunity for her, but she misses it by blaming the therapist as though the therapist is there to bring harm to the kid. She never stops to ask, “Do parents identify their kids by their diagnosis because it helps them feel something they’re craving?” She never posits that the problem may be bad parenting and not bad therapy.

She willingly, almost hypocritically, points out the pressure society puts on parents. “The culture devises ways to denigrate us,” she laments on page 248 after spending nearly 250 pages denigrating parents who might think therapy could help their kids. This is the pattern of the book.

She fantasizes about how great Gen X is doing—of whom I am a proud member—and ignores the very real research that suggests Gen X has some problems.

The Good:

After the long section of my problems with the book, you might think I hated this book, and I don’t think anyone should read it. And I would never suggest that someone should not read a book. I love engaging in ideas, even ones with which I disagree. Part of me wanted to like this book, and most of me was extremely frustrated by her tone, aggressive use of half-truths, and downright bad logic. With that said, there is quite a bit that we need to consider regarding our kids, parenting, and therapy.

Our society tends to think that experts are right simply because they’re experts. This creates an almost worshipful experience of the expert and expertise. While she doesn’t come out and say this exactly, she implies it, and I tend to agree with her. She calls into question the results that therapy is currently achieving and strongly calls into question our society’s obsession with removing sadness or any negative feeling from our world.

She does a great job of pointing out that anxiety is a normal body response. She claims that depression is a normal response (I’m not sure where I sit on this idea). She points out that the criteria for the use of medicine used to be chronic symptomology. I am old enough to remember when we couldn’t diagnose adolescents because their body chemistry was still too much in the development phase.

She calls out our society for thinking that every misbehavior is a medical issue, not a character or maturity issue.

She points out that many school systems seem bent on being the primary influence on our children (but she doesn’t seem to want to address the fact that there are many disconnected parents). She also ignores the fact that there are good school systems; she seems to want to make all school systems the enemy.

Not everyone needs therapy.

She drives the point home that not everyone needs therapy and is invested in ensuring this point gets across. I agree with her. I can think of multiple times over the years I have stated emphatically to adult clients and parents of adolescent clients, “You don’t need to be in therapy.” I have a long waitlist and want to help as many people as possible. I believe this is true of most therapists (they want to help people; I clearly cannot speak to their waitlist). The point remains: not everyone needs therapy. As I have stated publicly in podcasts and other blog posts, we have lost the word sad in our world. We go straight from happy to depressed. Being sad doesn’t mean you need to see a therapist. The result of our unwillingness to be sad is that we are losing resilience, which is another salient point of this book. She implores us to raise more resilient kids. I could not agree with this more.

Parents should be cautious about who interacts with their children, be willing to ask questions and be involved in the school process.

This is a brilliant and excellent part of the book. Parents need to be involved in their kid’s education in ways that seem counterintuitive today. She writes about how she doesn’t help with her kid’s homework. It’s on them to get the assignments done. It’s on them to succeed or fail. I love this. She writes about why our kids need us to let them fail and suffer minor distress. She rightly talks about the benefits of this for the adults they are becoming. Again, on its own, it’s a brilliant section.

She begs the reader to let the kids really and truly play. Let them struggle without creating a false world for them to live in. “…Things that are joyful to children: danger, discovery, dirt. Games whose rules they invented with that ridiculous cast of characters they call friends. Their hearts aren’t fooled by Mom’s carefully arranged simulacra: the hypoallergenic, nontoxic ‘slime’ she begs all the kids to make with her from a kit that arrived from Amazon. Isn’t this fun? It’s so gross! Right, girls?! Harmless enough, but it doesn’t help a kid blow off steam or, test her limits or negotiate relationships with peers. It doesn’t help her learn about herself and, in the process, discover what sorts of activities or people she might one day come to love.” (p.54)

We need to teach coping and resilience.

At the risk of overstating it, this is a great strength of this book. Our teens, young adults, and even adults struggle to develop coping skills. She calls for parents to let their kids fail. Let them fail in areas where they will experience pain because that pain produces coping skills and resilience in the adults those kids are becoming.

She calls us to revel in our kids. If you’re not enjoying parenting, something is wrong. This, of course, isn’t to say that we will enjoy every minute of it, but it should be an enjoyable experience. She points out that parenting is not a consumer experience but something to be engaged in, which calls us to a higher experience. It’s about something greater than us. She shares a story about a plane experience where a child yelled, and when Dad tried to work it through with the child, she never heard him bring up other people on the plane. Besides pointing out that just because she didn’t hear it doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, I agree that our society needs to do a better job raising kids who are mindful of other people.

She accurately calls society out for being too driven by emotions and bemoans how driven by our feelings we seem to be teaching our kids to be. She swings at this issue and misses it, though, because she seems only to be able to posit that it is altogether one hundred percent the failings of therapy and schools only!

She forces us to look at some hard questions.

The best strength of this book is that it forces us to look at some hard questions. We are at a time when the most energy and resources are being utilized for mental health, and it doesn’t seem to be producing results in commensuration with those efforts. Too many of my colleagues and other childhood development experts seem unwilling to engage in that conversation. If Shrier uses all-or-nothing rhetoric to bring the problem to light, too many use the same device to pretend that the problem doesn’t exist.

Summary:

I appreciate that this book forces a conversation about therapy, parenting, and schooling. I fear the conversation will happen despite the book and not because of it. Shrier’s approach is razed earth. She doesn’t meet a logical fallacy that she isn’t willing to use, and worse, she seems to be willing to present some therapeutic approaches dishonestly. She accurately points out that there are bad therapists, but then she lumps it all together. The thesis of this book is not, “There are some good and bad therapists,” it’s “Therapists are bad! You don’t need them; you never did.” She does give one minimal and quick concession in her author’s note. As I wrote above, It would be similar to writing a book about how all investigative journalists are bad because I can find some that were/are dishonest. It’s a fallacy.

On the whole, it was an incredibly frustrating read. Whenever I started to agree with something or find a point worthy of rumination, she would go rogue. There is a danger in this book. I am sure there are going to be people whose child needs therapy or who need therapy themselves who are going to use this book as justification for why they don’t need to do it. She completely dismisses ACE scores by minimizing words and purporting that there might be evidence to suggest that supports her while ignoring the evidence that disagrees with her.

She also shoots herself in the foot because I am sure my liberal friends are going to dismiss the book because her far more conservative leanings are transparent (I’m certainly right of center, and I found myself cringing). They will lose the valuable opportunity to examine important issues and ruminate on them. (If you read the book, you’ll see that Abigail hates the idea of rumination, but I believe it is valuable.)

The most egregious sin Shrier commits is that she seems unwilling to admit that there are bad parents out there. There are neglectful parents, and they are on the rise. She completely ignores this category of parenting styles in the book. She acts like it doesn’t exist. She accurately points out that there are schools out there that overreach, but she stubbornly points to only one possibility of why that is. She only points to rogue “interlopers” intent on destroying all that is holy and wholesome about the past. It’s the machines! Nowhere in the book does she point out that it could be because there are ever-increasing numbers of neglectful parents.

The reader is presented with a work that could have been a great book. In its current state, it’s just one more book to add to the list of things done to help us divide ourselves. Too many of my conservative friends will swallow it hole, missing the bones or perhaps choking on them because it takes to task those “crazy liberals!” Too many of my liberal friends will dismiss it, completely missing the morsels of meat that exist in it because of those “crazy conservatives!”

After reading it, I found myself sad, something that Ms. Shrier would no doubt tell me to get over.

[ctct form=”957″ show_title=”false”]

Proudly powered by WordPress

Do you actually think she makes good points or are you just saying that to appease your conservative readers?